Canada is on track for another record-busting year of euthanasia deaths.....

By JAMES REINL, SOCIAL AFFAIRS CORRESPONDENT, FOR DAILYMAIL.COM PUBLISHED: | UPDATED:

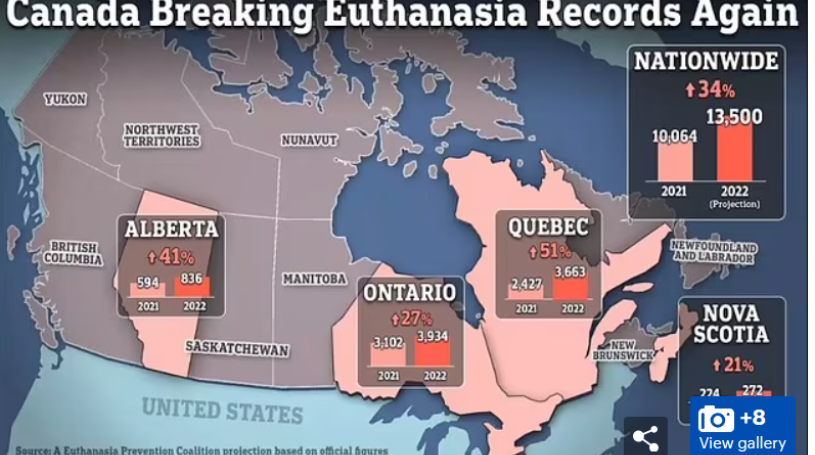

Canada has seen another record-busting year of euthanasia deaths, with a 35 percent rise to some 13,500 state-sanctioned suicides in 2022, an analysis of official data shows.

Canada's health chiefs won't release their formal tally for some weeks, but data from Ontario, Alberta, Quebec, and Nova Scotia already show steep rises in euthanasia deaths last year.

Based on those numbers, the Euthanasia Prevention Coalition, a campaign group, assessed that Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) cases rose from 10,064 in 2021 to some 13,500 in 2022.

They shared this projection exclusively with DailyMail.com.

Canada has one of the world's most permissive assisted suicide programs. Critics say it's on a perilous road to mass euthanasia and ever-more pressure on the sick, disabled and poor to end their lives prematurely.

Alex Schadenberg, director of the coalition, said euthanasia rates were 'skyrocketing' because a 'heavy promotion of MAiD within our medical system' had 'normalized' lethal injections.

'Every major healthcare institution has a MAiD team which will literally approach everyone who may qualify for MAiD and ask them if they want to die,' Schadenberg told DailyMail.com.

Daniel Zekveld, an analyst with ARPA Canada, a Christian advocacy group, said Canada had created 'one of the most permissive euthanasia regimes in the world' where deaths 'steadily rise.'

'Safeguards continue to be relaxed and euthanasia is increasingly offered as an easy solution to suffering,' Zekveld told DailyMail.com.

'Instead of normalizing euthanasia and accepting the deaths of thousands of Canadians, Canada needs to promote suicide prevention and life-affirming care for all.'

Health Canada, the federal government agency, did not immediately answer DailyMail.com's request for comment.

It is expected to release its count of euthanasia and assisted suicide deaths early next month.

Alberta, Ontario, and Quebec are among Canada's most populous provinces.

All recorded big increases in adults with a serious illness, disease, or disability opting for euthanasia last year.

Quebec saw a 51 percent uptick in MAiD deaths, from 2,427 in financial year 2021 to 3,663 in 2022.

That means some 7 percent of all deaths in Quebec are state-sanctioned, making it the third top cause of death in the province after cancer and heart disease.

Many Canadians support euthanasia and the campaign group, Dying With Dignity, says procedures are 'driven by compassion, an end to suffering and discrimination and desire for personal autonomy.'

But rights groups say the country's regulations lack necessary safeguards, devalue the lives of disabled people, and prompt doctors and health workers to suggest the procedure to those who might not otherwise consider it.

Some of Canada's euthanasia cases have courted controversy.

Alan Nichols, a 61-year-old with a history of depression, was greenlighted for a death by euthanasia due to his hearing loss in 2019, over objections from his family.

Christine Gauthier, a veteran and former Paralympian, sensationally revealed last year that she was 'shocked and in despair' after her caseworker offered her MAiD.

At the time, she was complaining about delays having a wheelchair lift installed in her home.

Canada's politicians are currently weighing whether to expand access to MAiD to include children and the mentally ill.

Canadians are largely behind euthanasia policy, polls show. A survey released in May showed that more than a quarter of voters said the poor and homeless should be allowed to end their lives with MAiD.

Canada's road to allowing euthanasia began in 2015, when its top court declared that outlawing assisted suicide deprived people of their dignity and autonomy. It gave national leaders a year to draft legislation.

The resulting 2016 law legalized both euthanasia and assisted suicide for people aged 18 and over, provided they met certain conditions: They had to have a serious, advanced condition, disease, or disability that was causing suffering and their death was looming.

The law was later amended to allow people who are not terminally ill to choose death, significantly broadening the number of eligible people.

Critics say that change removed a key safeguard aimed at protecting people with potentially decades of life left.

Today, any adult with a serious illness, disease, or disability can seek help in dying.

Schadenberg said MAiD teams in clinics were aggressively pushing for sick people to opt for euthanasia.

He described cases of medics asking terminally sick people as many as five times if they wanted to end their lives. In some cases, they asked them when relatives were present, and again when alone, Schadenberg said.

'The selling of MAiD by the MAiD teams is a big reason why the numbers are skyrocketing.

'If you're going to pay people to be on a MAiD team, they will sell what they are offering,' Schadenberg said.

Euthanasia is legal in seven countries — Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand and Spain — plus several states in Australia. It's only available to children in the Netherlands and Belgium.

Other jurisdictions, including a growing number of US states, allow doctor-assisted suicide — in which patients take the drug themselves, typically crushing up and drinking a lethal dose of pills prescribed by a physician.

In Canada, both options are referred to as MAiD, though more than 99.9 percent of such procedures are carried out by a doctor. The number of MAiD deaths in Canada has risen steadily by about a third each year from the previous year.