10 Teens Gave Up Smartphones for a Month. Here’s What Happened

Guest post by John-Michael Dumais

British journalist Decca Aitkenhead offered a compelling glimpse into how digital detox can transform young lives — and maybe address what social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, Ph.D., calls “the anxious generation.”

In a bold experiment that addresses the growing concerns about smartphone addiction and teen mental health, British journalist Decca Aitkenhead challenged her two teenage sons and eight of their friends to go without smartphones for a month.

The results, published this month in the U.K.’s Sunday Times Magazine, offer a compelling glimpse into how digital detox can transform young lives — and potentially address what author Jonathan Haidt, Ph.D., calls the “anxious generation.”

Aitkenhead’s experiment, inspired by Haidt’s research on teen mental health trends, didn’t just take away cellphones. It culminated in an unsupervised camping trip that pushed boundaries of independence rarely seen in today’s overprotective parenting culture.

The outcomes surprised the teens and adults involved, and revealed unexpected resilience and joy in disconnecting from electronics, according to Aitkenhead.

“I’m really glad I did it,” one participant told Aitkenhead. “It was way better than I expected.”

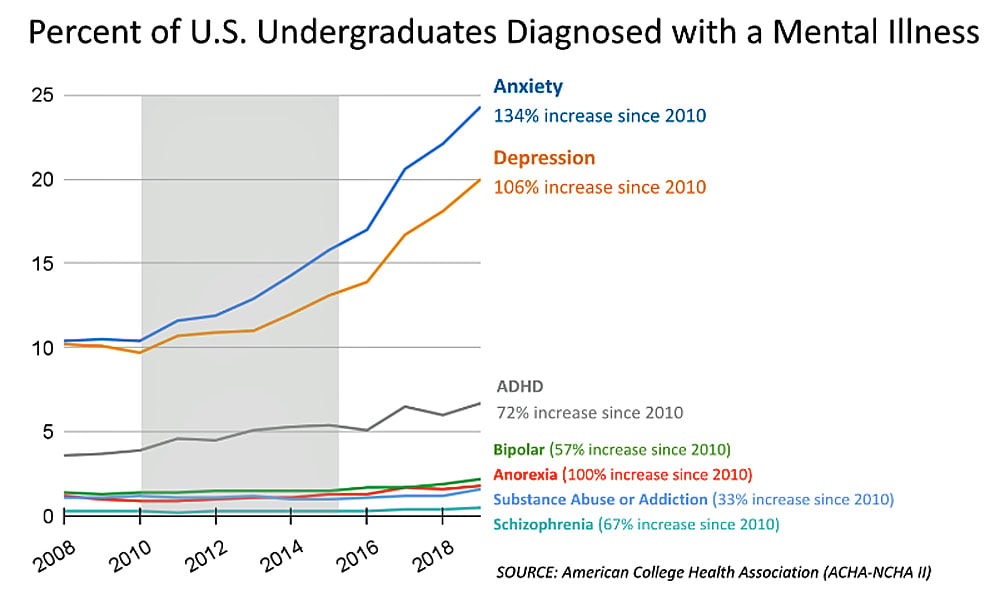

This real-world test of Haidt’s theories comes at a crucial time. Recent data show rates of anxiety and depression among teens have more than doubled since the early 2010s, coinciding with the widespread adoption of smartphones and social media.

As parents and policymakers grapple with the crisis, experiments like Aitkenhead’s offer hope and practical insights.

‘Like a glitch in the matrix’

Haidt, a social psychologist at New York University’s Stern School of Business, has been sounding the alarm about a dramatic shift in teen mental health. His 2018 co-authored book, “The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure,” was a New York Times bestseller.

In his latest book, “The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness,” Haidt presents compelling evidence of a crisis that began with the rise of children’s widespread use of smartphones and social media.

“We see a very sudden shift in the early 2010s — it really is like a glitch in the matrix,” Haidt explained on the “Triggernometry” podcast. He argued that a “great rewiring of childhood” occurred during this period, deeply affecting children’s self-concept and social skills.

Data from the U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health reveal the percentage of teens experiencing major depressive episodes has more than doubled since 2011. Similar trends are observed in the U.K., Canada and other developed nations, according to Haidt’s research.

Credit: The Anxious Generation

Haidt suggested this isn’t just about mood disorders. Rates of self-harm, suicide attempts and feelings of loneliness have all surged among Gen Z, defined as those born after 1996.

‘To my sons’ horror, I devised an experiment’

To test Haidt’s theories, Aitkenhead hatched an audacious plan involving her sons Jake, 14, and Jody, 13, along with eight of their friends ages 13-15.

“To my sons’ horror, I devised an experiment,” Aitkenhead wrote. The teens’ initial reactions ranged from reluctance to outright panic. “No way are my friends doing that,” Jake told her. “You can’t.”

For one month, the teens locked their smartphones in time-lock containers, accessible for only one hour daily. They were instead given basic “Light Phones,” a type of “dumb phone” that allows only calls, texts and other minimal functions.

Recruiting participants proved challenging, especially among girls. Aitkenhead noted this difficulty might reflect the deeper hold social media has on female teens.

Eventually, two girls joined the experiment, providing crucial insights into gender differences in smartphone use and its effects.

Aitkenhead discovered that while boys primarily used their smartphones for Snapchat, Spotify and sports videos, girls spent significantly more time on social media platforms. This seemed to have a more profound negative impact on the girls’ mental health and self-image, which lines up with Haidt’s research findings.

The two-day unsupervised camping trip tested the teens’ ability to navigate the real world without constant digital connection. This aspect of the experiment addressed another key concern in Haidt’s work: the loss of independence and free play in modern childhood.

Haidt shared these points in an introduction to an article about the unsupervised smartphone-free camping trip by Lenore Skenazy and Haidt on Haidt’s “After Babel” Substack.

Skenazy is the author of “Free-Range Kids: How Parents and Teachers Can Let Go and Let Grow” and the co-founder with Haidt of Let Grow, a “movement for childhood independence.”

‘Whatever’s going on on your smartphone doesn’t matter’

The month-long digital detox yielded surprising results. After some initial struggles, the once-skeptical teens found unexpected benefits in their smartphone-free lives.

“You start to see that whatever’s going on on your smartphone doesn’t matter,” said Lincoln, a 14-year-old participant. “You’ll never say on your deathbed, ‘I wish I’d spent more time on my phone.’”

Many reported feeling less tired and more focused. Rowan, another participant, read a 700-page book about basketball during the time he would have spent scrolling through his social media feed.

Isaac, 14, felt “streamlined” and more efficient in his daily tasks. “It was just calming. It flattened everything out.”

The unsupervised camping trip proved particularly transformative. Despite initial doubts about the teens’ competence, they demonstrated remarkable growth, “In under 36 unsupervised hours, they appear to have grown up by about two years,” Aitkenhead said.

Although several kids later reported finding it challenging not to slip back into old patterns, at the end of the trip, all of them said they hadn’t missed their cellphones. Most had even stopped taking advantage of the daily smartphone hour.

The two girls had the most difficulty with the smartphone-free month but seemed aware of the dangers. Rose, 13, told Aitkenhead, “Why would you give your child a phone? … If you realise how harmful it is — just pressure and nicknames and labels and impossible standards — why would you give your kids that?”

‘All the experiences that a kid needs get blocked out’

During the conversation on “Triggernometry,” Haidt pointed to how smartphones with front-facing cameras have affected teens. “All the experiences that a kid needs get blocked out by this.”

He said the issue goes beyond mere distraction — constant smartphone use during crucial developmental years can impair the growth of executive function and social skills.

“What we’re doing to kids … is going to hurt them for the rest of their lives,” Haidt said. He cited concerns with attention fragmentation, delayed maturity, impaired creativity and risk assessment, and vulnerability to exploitation (like sextortion).

He noted that many employers report difficulties with Gen Z employees due to issues with anxiety, initiative and problem-solving.

The societal implications of inaction could be severe, Haidt warned, including plummeting rates of marriage and childbearing.

“What we’re talking about really is civilisational collapse. If things keep going the way they’re going, then yes …we will have an ever-shrinking population of more anxious people.”

‘We need to delay it’

Despite the sobering statistics, Haidt remained optimistic about potential solutions. He proposed establishing four key norms:

- No smartphones before high school (around age 14) — flip and dumb phones are OK.

- No social media accounts until age 16.

- Phone-free schools with restricted or zero use during the school day.

- Give kids far more independence, free play and responsibility in the real world.

“If we do those four things, we can actually fix this problem in the next year or two,” Haidt said. “We’re not going to burn the technology, [but] we need to delay it.”

He suggested coordinating with other parents in “collective action” to create screen-free opportunities for children to socialize. “That’s going to be a very lonely life unless you have a few other families” practicing the same norms.

Even just starting with a day or two at a time can make a difference with teens, Haidt said, noting that it can be “fun, and that’s what we have to give them back.”

The Anxious Generation website offers free resources for families and educators, podcasts, a newsletter and connections to aligned organizations.